Afghanistan, historically, has been synonymous with turmoil and conflicts. The unending trail of conflicts continue unabated and the Taliban’s march into Kabul is nothing more than the beginning of yet another chapter in the country’s violent history. For the time being, the Taliban is in control of large parts of Afghanistan and a loose political structure may soon emerge.

In the short term, Taliban may even succeed in ‘imposing’ normalcy in Kabul. But, as the euphoria of victory fades away, deep-rooted ideological incompatibility between ethnic groups and different factions, leadership rivalries as well as the deep scars of social and psychological wounds inflicted by the Taliban will come to the fore. Investment in nation-building is bound to be an uncomfortable and worthless exercise for the Taliban and a low priority agenda even for the international community. Reconstruction of Afghanistan and development of a long-term sustainable economy are, therefore, likely to remain unaddressed.

Away from its cities and highways, rural Afghanistan has always remained a scattered, self-reliant entity of social units, best described as ‘village-republics’. Rural Afghanistan has never been integrated with the mainstream, least of all economically. Historically, life in rural Afghanistan has largely remained unaffected by the events and happenings in Kabul and other Afghan cities. The country’s borderlands population have a very strong kinship network across the borders and maintain far closer social and economic bonding with people across the border than with those within the country. No Afghan government has ever recognised the Durand line. Some even perceive the city of Quetta across their Eastern borders with Pakistan to be theirs. Apart from the security dimension, porous borders also have severe implications on the country’s economy.

Before taking a deeper look at Afghanistan’s economy, an overview of the country is essential. Afghanistan has an area of about 650,000 sq km, equivalent to the Indian states of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh put together and a population of about 35 million, comparable with that of Kerala or three times that of Uttarakhand. It has a density of population of 46 per sq km compared to 17 of Arunachal Pradesh or 382 of India (2011 figures). With a GDP (Nominal) of about $20 billion which is close to that of Himachal Pradesh or just about 1/6th that of Kerala and a per capita GDP of less than 25% of India, Afghanistan remains one of the poorest countries in the world. The traditional sustenance agricultural economy of rural Afghanistan has been almost totally destroyed due to mass migration, frequent bombings and scattered mines.

Scholars point out that Afghanistan has been living on external aid for over 100 years now. First came the British who paid off the emirs to maintain a good relationship in the region and to facilitate their trade routes as well as to maintain a degree of hegemony. Then came the Soviets with aid and chaos. They were followed by the Americans with huge reconstruction objectives and more aid and turmoil.

The question now is who will follow next? Will it be the Chinese? From whatever the world has seen of China, the Chinese philosophy for economic aid recognises only the loan route and not the financial aid route. There is not a single example so far where China has assisted any country in its economic revival. There is no reason to believe that an exception will be made for Afghanistan. After all, as of now, China is itself, still some distance away from breaking the middle-income barrier.

A look at Afghanistan’s budget for the year 2018 is indicative of the country’s continuing hunger for external aid. Of the total revenue of 353 billion Afghani (AFN), external grants and aid comprised 191 billion!! While external aid catered for almost the entire development budget, even for day to day running of the country, close to 40% of the operating budget was funded through external aid.

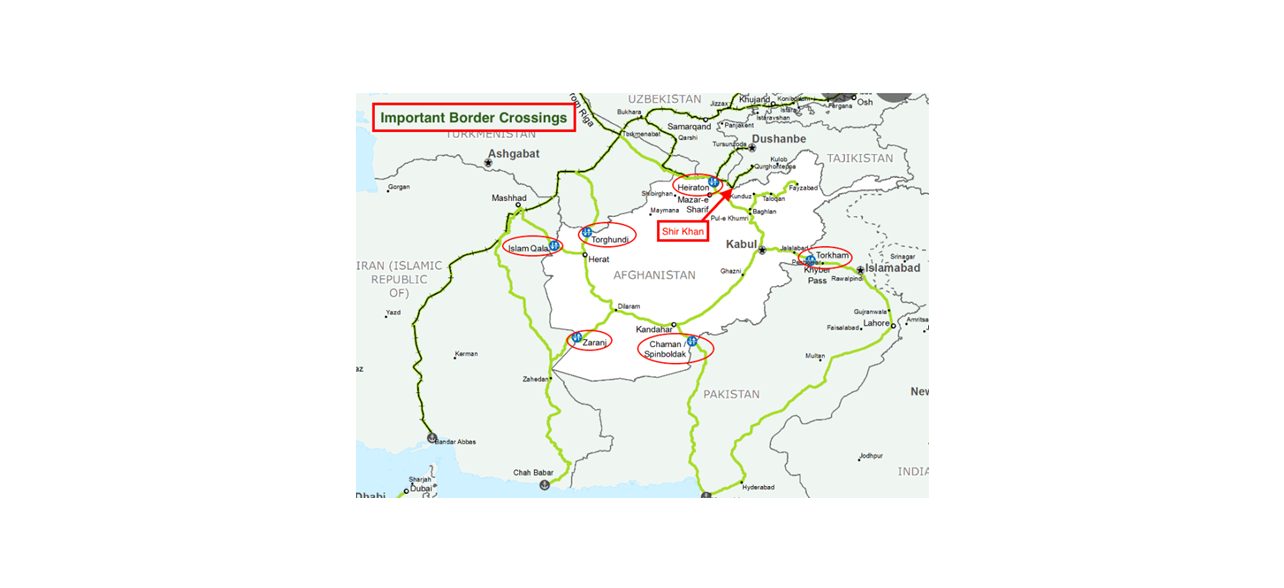

The biggest source of income after external aid is revenue from Customs duties which underlines the importance of border check posts for a country like Afghanistan.

Another significant facet of Afghanistan’s economy is its security-related expenditure which in 2018 was a huge 28% of its GDP; in comparison, similar low-income countries spend only about 3% of their GDP on security. International troops deployed in Afghanistan made a considerable contribution to the Afghan economy. A decrease in the level of foreign troops invariably witnessed a corresponding decrease in external aid. Aid inflow was 100% of GDP around 2009 when the troop level was high. With troop level dropping to about 10,000 by 2020, aid flow too dipped to just about 40%. Foreign troops contributed to the economy in many other ways too. The Bagram airbase which was vacated during last week June 2021, was the source of employment for over 30,000 locals in the area.

Afghanistan, today is faced with multi-dimensional poverty, in terms of income, health care, education, security and freedom. Decades of war and turmoil has created an open war economy in the country. The war economy, as is its nature, has structured itself to bring economic returns to the perpetrators of the conflict.

The most important pillar of Afghanistan’s war economy is its Drug economy. Almost 85% of the world’s opium production comes from Afghanistan. As per a 2015 UN report, Afghanistan is the producer of the entire opiates consumed by countries along the Balkan drug route. Balkan drug route emanates from Afghanistan and goes to Southern and Eastern Europe via Iran and Turkey and the annual drug trade on the Balkan route is valued at a whopping $28 billion. However, of this $28 billion, about $8 billion goes to the Iranian traders, about $18 billion to the retailers in Europe, about one billion to the traders in Turkey and only about half a billion comes to Afghanistan, the fountainhead of global drug mafia and even of this, only a very small fraction trickles down to the actual poppy cultivators. A 10% ‘tax’ is imposed by the dominant groups in their respective areas on every link in the drug chain starting with the farmers, the labs, traders at various levels and on transportation.

The second pillar of Afghan’s war economy is illegal mining. Afghanistan has considerable mineral wealth, assessed at about $1 trillion which remains largely untapped. Afghanistan is rich in Iron ore, Aluminium, Lithium, Talc, Gold, Uranium and also has some Rare earth deposits. While the extent of official government mining in Afghanistan has been insignificant, there are numerous small, informal, illegal mines. Mining and drugs, together provide the lifeline for the Taliban and even entities like the Islamic State (Khorasan).

Afghan government’s loss of revenue due to rampant corruption even from its modest official mining revenue is huge and details of the country’s official coal export to Pakistan tells the story. While the Afghan government’s official figures for coal export to Pakistan for the period 2015-2018 was $30 million, the Pakistan government’s official figures for its coal import from Afghanistan for the same period claims it to be $68 million. Similarly, Afghanistan’s official export price of coal to Pakistan for the period showed $42 per ton while Pak government figures showed $87 per ton. As a result of such rampant and all-pervasive corruption, Afghanistan’s annual revenue from mineral mining is a mere $42 million while its assessed revenue loss due to corruption from the officially mined minerals is pegged at $125 million annually.

The third pillar of Afghan’s war economy is Transit trade in the form of Customs Duty that accrues from import and export through its border check posts. Customs duties comprise the second biggest source of national revenue after foreign aid. In June 2021, the Afghan government collected $91 million from customs revenue. However, just a month later, in July this year, as the border customs ports started falling into the Taliban’s hands, this revenue fell to about $30 million.

There is also a huge flow of smuggled consumer goods that go from the global duty-free hub of Dubai to Pakistan through Afghanistan which also contributes through illegal transit income to the war economy.

Beyond these main pillars of war economy are the related service sectors which are stimulated by the drug trade and illegal mining and include transportation business, fuel stations, shops, eateries etc who are required to pay ‘extortion taxes’.

Taliban’s source of revenue is a true reflection of Afghanistan’s war economy. Its total revenue in 2019-2020 was assessed at $1.6 billion with drugs and illegal mining contributing over $400 million each. Extortion taxes bring in about $150 million. Every activity such as media, shops, government projects, businesses, land, wealth, travel etc attracts this ‘extortion tax’. In fact, even journalists reporting from Kabul or elsewhere in Afghanistan are required to pay extortion tax and obtain clearance and journalist passes issued by the Taliban. Taliban’s revenue in the form of ‘Charitable donations’ from Islamic organisations around the world is about $250 million. In addition to all this, it also receives direct funding from some Islamic governments.

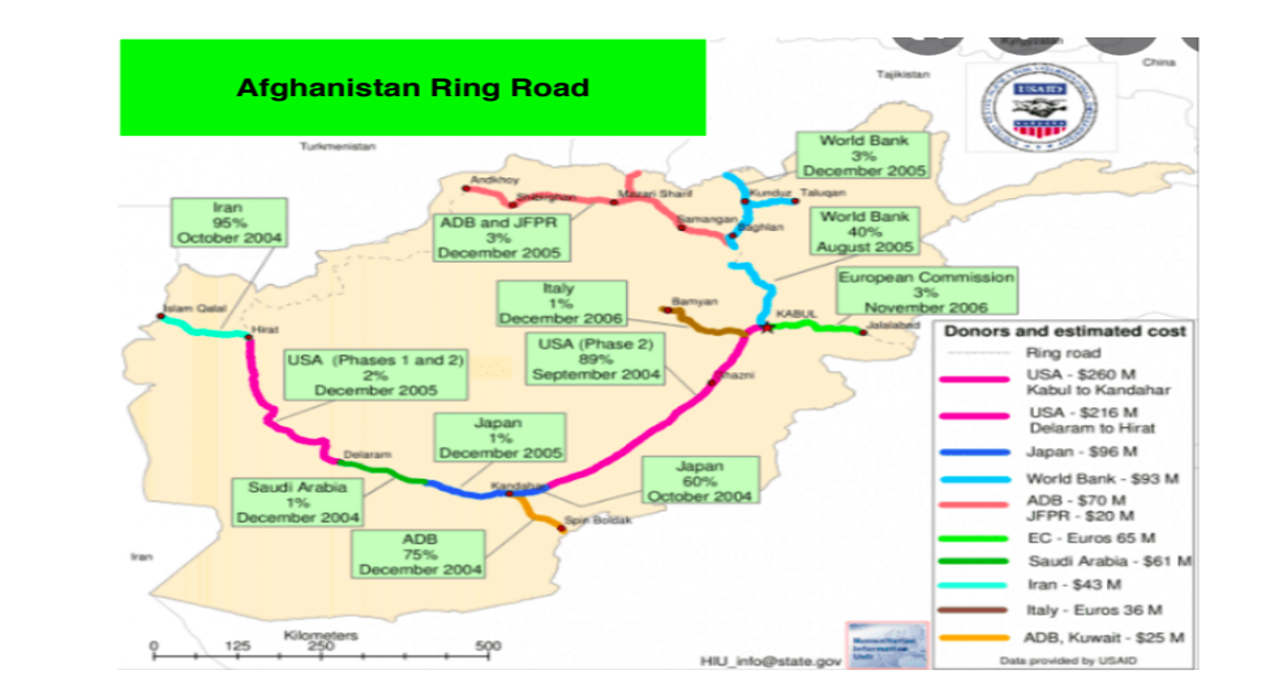

In the context of Afghanistan’s war economy, the country’s highways also play a unique role. Being a landlocked country, highways are critical to Afghanistan’s economy. The construction of a 2000-mile-long ring road in Afghanistan was started by the Soviets in the 1950s. However, due to perpetual turmoil, only a handful of stretches could be completed and that too remained very poorly maintained. The state of roads in Afghanistan was so pathetic that in 2001, the country had just about 50 miles of good road.

Post-2001, the US along with Japan, World Bank and other countries made an ambitious $1.5 billion plan to complete and upgrade the Ring Road. Kabul-Kandahar was identified as the most important segment and was to be completed by 2003. The work commenced in real earnest but soon ran into serious problems as the Taliban started targeting through kidnappings, killings, ambushes and IED attacks on engineers and workers. This imposed huge additional security costs which in turn skyrocketed the road construction costs. Despite the disruption, the Kandahar stretch was completed in 2003.

But then Iraq happened and the US focus shifted to Iraq and as a result reconstruction tempo in Afghanistan reduced. Taliban exploited the opportunity by increasing the frequency of attacks on the highways in the form of blowing up roads and bridges. By 2016, the ring road had turned into a highway of potholes, debris and ambush points. By then, the state of the ring road and the government’s lack of control over it had become an accurate reflection of Afghan government’s influence and capacity.

As the level of foreign troops dipped sharply after 2013, the Taliban tightened its sway over the ring road and even claimed its ability to guarantee safe passage for anyone who sought and paid for their protection, a claim which locals endorsed to be true. It is believed that if you paid the Taliban a one time “advance tax” of $75 for a one-way vehicle move, you were assured of a safe trip. While on the other hand, if you ignored the Taliban and trusted the Afghan troops, you would end up paying $15 to $20 bribe at each of the 12 Check Posts to Afghan troops manning these posts and that too with no guarantee of safety for your movement between the Check Posts.

Between 2001 and 2020, the US alone reportedly pumped in a whopping $134 billion for the reconstruction of Afghanistan. Sadly, there is very little to show for it. It is an irony that a large part of this American taxpayer’s money has actually ended up funding the very same Taliban that their troops were fighting.

Gardez – Khost highway bears testimony to this fact. Gardez – Khost road is a 60-mile stretch connecting Afghan’s Eastern borders with the ring road. The construction agency was Louis Berger Group (LBG). The work started in 2003 but could be completed only by 2015 that too at a huge cost of about $5 million per mile. There is a court case in the US alleging that the firm paid a huge amount as protection money to the Taliban and possibly even the Al Qaida, to permit unhindered road construction. It is possible that under pressure to complete the project, LBG felt compelled to indulge in this crime.

The end result of all the money that has been sunk into Afghanistan is best summed up by a local who says ‘before 2001, we had only a dirt track as the Ring Road, but it was safe for travel and one could pull up to a side and sleep at night. Then came few stretches of good roads after 2001. But now in 2020, the roads are totally damaged, pot-holed and far worse than our pre-2001 dirt tracks, with the added risk of a bomb blast or attack at every turn’.

Poverty in Afghanistan was 54% in 2017 and the economic situation has turned far worse in 2021. Unlike a political agreement that may be possible overnight, there are no shortcuts to an economic revival. Afghanistan’s economy is on a Razor’s edge. What can a Taliban led government do in economic terms? With even semblance of a governance system or a financial institution worth the name non-existent, the economic journey ahead looks very long and steep. To make things worse, the private sector and human capital have vanished, negating any possibility of creating and mobilising domestic resources. Afghanistan today, is in greater need of external aid than it had ever been before. Even if generous aid flows in, basic service delivery will prove a herculean task.

China finds itself in a quandary in many ways. As events unfold, it would be interesting to see if the geo-economic and geo-political situation compel China to risk investing in Afghanistan’s reconstruction. Will the Islamic nations come together to help? Will the rest of the world come to Afghanistan’s rescue knowing fully well that the untrustworthy Pak-Taliban alliance would stand to gain the most from every dollar that flows into Afghanistan and China would be the biggest beneficiary of stability in Afghanistan and the region? Can the Taliban with its savagery image ever transform itself to permit a changeover of Afghanistan’s war economy into a formal economy?

Afghanistan’s economy holds the potential to become the Taliban’s Achilles’ heel. Economy and political stability pose a catch 22 situation. While political stability cannot be achieved without a certain degree of economic revival, economic revival itself requires far more than just political stability, sharia laws and the financial expertise of the Taliban. The writing is on the wall. Afghanistan’s economic burden is likely to remain an orphan and its economic revival, on a road to nowhere.

Lieutenant General CA Krishnan, PVSM, UYSM, AVSM (Retd), is a former Deputy Chief of the Army and a former Member of the Armed Forces Tribunal. He has been on the Board of Directors of Bharat Electronics Ltd and Bharat Dynamics Ltd, two of India’s leading Defence Public sector undertakings. He is a prolific writer on a wide variety of subjects like strategic issues, Rare Earths, Space mining, Energy, Population etc. He also advises defence industries seeking to expand / streamline their existing defence manufacturing base as well as potential entrepreneurs contemplating entry into the defence manufacturing arena.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are author’s own and do not reflect the views of IIRF. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. Originally published at Chanakya Forum. This is a reprint.

………………..