When Albert Einstein remarked that politics is harder than physics, he had in mind the enormous number of variables that the statesman and strategist must consider while studying international phenomena.1 Belt and Road Initiative of China along with the myriad of reactions that it attracts from all quarters, is a testimony to this fact.

In 1992, American political scientist, Francis Fukuyama in his essay End of History had argued that liberal democracy as a system of government had emerged throughout the world, conquering rival ideologies like hereditary monarchy, fascism, and most recently communism. He further felt that liberal democracy, therefore, constituted the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution.2 Liberal intellectuals world over had also started believing that the post cold war international environment represented the final triumph of liberal democracy over its twentieth-century ideological competitors, fascism, and communism.3

Notwithstanding, China’s economic performance in the first quarter of the 21st century coupled with its successful comprehensive poverty alleviation program4 for its burgeoning 1.39 billion people through a one party system, has put a question mark on Fukuyama’s, once popular and widely held perception.

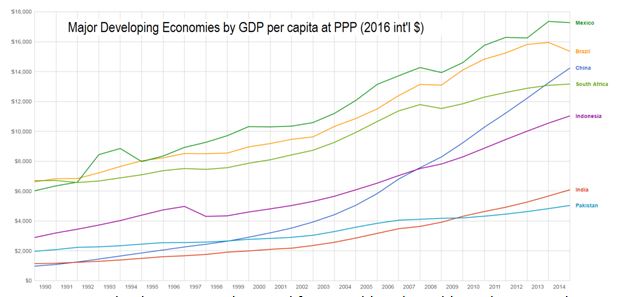

Sequence of events leading to the spectacular economic rise of China had started manifesting itself to the world from the beginning of the 21st century itself. (figure 1) However, the start of this process can be traced back to 1970s when the reclusive agrarian Chinese society was pulled out of its bamboo curtains and nudged to get integrated into the global economic system in 19725. This was done deliberately by the then American administration partially to wean away china from Russia but also with the high hopes that an economically prosperous China will make the appeal for regressive communist system for its people, weak and redundant. Deng Xiaoping’s “domestic reforms” and “unleashing of market forces” were expected to push China towards an open society and an open market system. The above theory of President Richard K Nixon and his “shuttle diplomat” Mr Henry Kissinger, under whose influence it was propagated6, lies shattered today.

Figure 1 By CircleAdrian – Created on Excel from World Bank World Development Indicators 2014 data, CC BY-SA 3.0,

Not just that, but the very foundations of the capitalist philosophy, rooted in the uncompromising notion of the malevolence of communism over capitalism and its propensity to suppress the human spirit and dignity, also stands challenged once again. This has forced the academics and intellectuals from both liberal democrat as well as the conservative capitalist worlds, to go back to their original drawing boards to find the theoretical explanation for this phenomenon. Revival of the ancient silk road by China through its Belt & Road Initiative, is just one of the many controversial reference points in this big ideological debate of our era. Hence no serious study of BRI can be considered complete, without putting it in the above context.

Why BRI

Ever since introduced to the world by Mr Xi Jinping in 2013, the geo-political motivations behind Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China has come under heavy suspicion and criticism. Challenge for neutral academicians and observers, therefore, is to rise above the deluge of not so unbiased literature flooding the digital world on the subject. Challenge is to go beyond polarized views and to assess the true potential and geo-economic implications of the massive array of cross-national infrastructure projects envisaged under BRI in a more objective manner.

However, before dealing with the issue of impact of BRI on the global economy and geopolitics, it will be worth acquiring some perspective of the background in which BRI was conceived by the leadership of China at the first place.

The Economic Angle

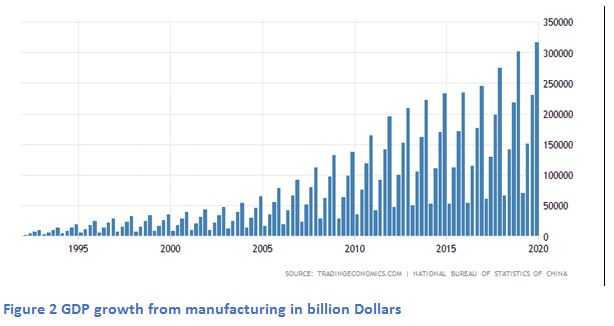

As already mentioned, one of the consequences of integration of China into the world of free market system in 1972 was that western capital and technology started flowing into Chinese economy liberally.7 Policies followed by Deng Xiaoping’ between 1978-1993 and his successors later, brought significant changes in the economic philosophy of China. It introduced economic liberalization and brought domestic structural reforms to accommodate market forces in sync with the world economy. His focus on globalization acted as a catalyst in mobilizing its massive national resources that lie idle and untapped till recently. Once invoked, the hitherto lying idle man, material and intellectual resources unleashed its economic potential as never before8. China was able to modernize and scale up its manufacturing rapidly and took its domestic industrial output to unprecedented heights in a very short time. This was coupled with Chinese access to American and Western markets where, being an “under-developed nation” (at that point of time), it was granted the status of the most favoured nation (MFN)9. As a result, by the time China entered the 21st century, its economy had started manifesting extraordinary growth in all parameters of human development and industrial output. (figure 2).

Its GDP grew at a rate of an average of about 9.5% during the 90s (figure 3). By the year 2010, China’s Gross Domestic Product had quadrupled compared to what it used to be in 1995 (figure 4).

With a population of 1.39 billion people, it had already attained its per capita income (PPP) of $3,800. This made China the second largest economy in the world as it entered the 21st century. The fact that it will surpass USA in GDP terms sooner than later, remained no longer a matter of speculation.

But Chinese economy had to experience significant setbacks during the Asian financial meltdown of 1997-98. The susceptibility of Chinese domestic economy to the factors beyond its borders over which it had little control came to Chinese leadership as a rude shock. The national growth rate of its economy came down during this period from 14.3% in 1993 to 8.9% in 1997 it dropped to further 7.8% in 1998 and went on going down to 7.1% in 1999(figure 3).

The Chinese economy did recover impressively between 2000 and 2007 regaining its growth rate once again to a staggering 14% for a brief period of time in 2007, but then the global financial crisis recurred in 2008. US and Arab subprime crisis sent shock waves to the entire global banking and financial systems and the overall global demand and consumption started getting distorted. In a single year, China’s growth fell from 14 % to 9% and went on sliding year after year between 2008 to 2018 touching a little over 7.5 % in 2013. There were strong indications that global demand would go down further throughout the decade affecting the Chinese economy adversely. Marginal recovery made in the year of 2010 (i.e. 10.45%) were all but washed away. The Euro zone crisis of 2016-19 added further fuel to the fire. It had its own adverse effect on the global demand and put further pressure on the scales of Chinese exports10.

The fragility of economic growth of China and its precarious dependence on a volatile global market of contracting demand was amply revealed to the Chinese policy makers. It was clear to them that the global demand on which the Chinese economic miracle was being scripted, was not going to last long. It was clear that vagaries of west controlled global market system were going to affect Chinese economic growth and stability adversely in the years to come.

Bouts of global recessions had started raising barriers to international trade. Countries after countries started regulating their imports more stringently. Issues related to adverse trade balances started occupying centre stage in national and international debates. Protection of domestic industries and arresting domestic un-employment became the buzzwords in industrialized nations.11 Anti-China sentiments had started making inroads into American domestic politics and was ready to influence its foreign policy. Many nations in Europe and Asia too started questioning the Chinese commercial practices in their countries. Justification for continuation of China’s MFN status in America was questioned. China had understood that excessive dependence on traditional American and European markets were inadequate to support further Chinese growth. China had to do something about it.

In tune with the Chinese psych and their typical response when confronted with such massive national problems, amply demonstrated in their long history, the Chinese policy makers instinctively opted for something “BIG”. Since the existing global market based on Bretton Wood model was proving undependable and unmanageable to sustain Chinese economic growth, CCP under Mr Xi’s leadership, decided to create an entirely new global market system for itself which could remain under its control and which it could manage without outside interference – The idea of BRI was born!

Other Domestic Compulsions

China’s State-owned entities (SOEs) in the sectors like cement, steel and construction by the end of 2010 had accumulated huge overcapacities by expanding their mines, plants, factories and by expanding their construction work force to such high levels that it became unsustainable during bouts of economic slowdowns. These construction Juggernauts were created to serve the explosion of Chinese domestic construction activities during the early phases of economic expansion. However, as domestic market started getting saturated and demands for construction started to contract, these giant companies found themselves struggling to put their over capacities and surplus workforce to use. China during this period had also accumulated large foreign exchange reserves and domestic savings that lay underutilized both domestically as well as internationally. Investing in large-scale overseas infrastructure projects conceived under BRI made good sense for China and enabled it to export its excess capacities and savings to BRI member states that also promised to give a new lease of life to its limping SOEs and stressed domestic employment levels.

The Strategic Angle

As China’s growing industrial and manufacturing strength started competing with the progressively weakening western economies in a manner that could no longer be ignored, tensions grew in international relations specially between China and the US. Strategic analyst world over could no longer turn their eyes from the fact that a new chapter of cold war, in the history of global geopolitics had begun.

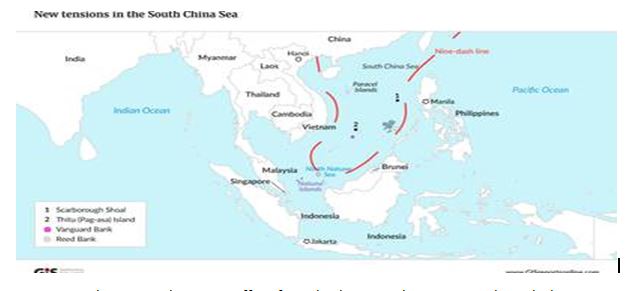

It is estimated that currently, approximately 80%of global trade by volume and 70% by value, are being carried by sea12. Of that, 60% maritime trade, relates to Asia alone. South China Sea itself transited an estimated one-third of global shipping. All this made the waters of South China sea strategically very crucial for China as well as its competitors and adversaries.

Moreover, the entire shipping traffic of South China Sea must pass through the narrow Straits of Malacca, which connects the South China Sea to Indian Ocean and on which bulk of its energy supplies and global trade depends.

China now being the second largest economy in the world with over 60 percent of its trade in value being transported by sea, was quick to realize that its economic security was closely tied to the international neutrality and freedom of navigation in South China Sea. To put it crudely – it meant nothing but freeing it from the external US domination and substituted it with the Chinese one. The high concentration of commercial goods flowing through the relatively narrow Strait of Malacca made it a vulnerable strategic chokepoint for China13. Therefore, in a situation of conflict, china could obviously not let “Strait of Malacca” become its “achilles heel”.

Yel University professor of International Studies, Nicholas John Spykman in 1942 had propagated the “Rimland Theory” and suggested – “Who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia, who rules Eurasia controls the destiny of the world14.” Ever since then, US geopolitics had remained anchored to this theory15. In line with this formulation, America has continued to exercise its world domination through its ability to control the Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs)round the globe. Naturally, if the international tension grew and a military show down with China became imminent, America and its allies, with their current dominance of SLOCs, were sure to use Malacca as a strangulation point to discipline China.

Viewed purely from the Chinese perspective, securing an un-hindered movement for its expanding global trade, energy supplies and navigational freedom finding a solution to its “Mallacan Headache” became one of the top strategic priorities of China. For Chinese strategists, this was not just a “navigational problem”. For them it was their “existential Problem”.

China’s civilizational pride and growing global stature was not giving them any comfort to find a leash put in their neck whose other end was in the hands of US and its allies. Alternative to this “Malaccan Dilemma”, had to be found and it was found in the BRI.

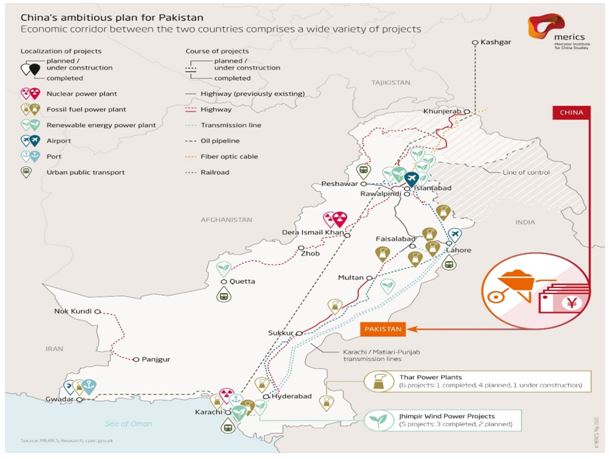

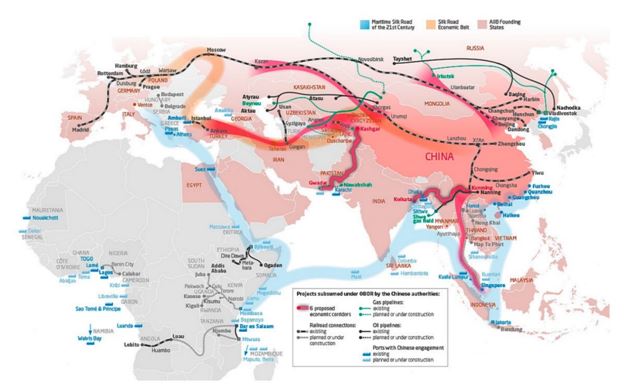

Under the Belt Road Initiative, China has stitched together a blueprint to build a series of ports and other strategic infrastructure in countries like Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan in Asia and a maritime silk route through the arctic.

On land the silk route is associated with high-speed rail and road links, energy pipelines and power grid connections all along the route connecting European continent directly to the north western regions of China through rapid land transportation system. to the Bay of Bengal and Arabian sea.

These land and maritime silk routes conceived under BRI are ostensibly for trade, but not hard to sense that they are likely to pave the way for China to set up many military bases along its SLOCs like the one it has built at Djibouti. When completed, China’s sole dependence on Malaccan strait will reduce and China expects a direct access from its north western mainland maritime silk road that closely resonates with its concept of “string of pearls”. These projects are expected to give China its much-needed maritime autonomy and navigational freedom that it feels will secure its economic interests, energy supply needs and maritime trade to Europe, Africa and South American markets.

Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a multinational infrastructure project of 140 member states led by China who have committed themselves to connect their economies through high speed rail, road, air, water, fuel, gas pipelines, power grids, ports and shipping lanes complete with all the peripheral trade infrastructures like transit posts, ware housing, supply chains, trade centres, free economic zones, industrial and production centres, with entirely new set of inter-governmental trade protocols with possibly alternative international currency as a means of exchange for trade and finance outside or parallel to the world Bank, IMF and other international trade organizations. BRI is China’s most ambitious and audacious attempt to revive the ancient silk route and integrate the Eurasia’s age-old natural economy with that of Africa by building and augmenting multiple cross-border trade routes linking the three continents. If implemented in its entirety as conceived, BRI is likely to have an unprecedented impact on the lives of the people of Asia (of which India is an integral part).

On critical analysis, it appears that over all Chinese objective is to establish a China-centric economic order16 in the Eurasian market in general but more specifically in Central Asia and South East Asia where it wants less American interference. For this, it is gearing itself up to compete with US to control the SLOCs in the South China Sea, including its choke points and hen move deep in the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific. The creation of artificial islands and their militarization and controlling the EEZs of other nations in the South China Sea are parts of this grand strategy to secure the necessary strategic autonomy and possibly military dominance on land and sea to achieve its full economic potentials without getting impeded by its hostile global competitors.

The Zero-Sum Game

The backdrop outlined above has given rise to some very pertinent questions vital to the evolving international equations and the shifting global power balance. Is BRI a zero-sum game in which someone must lose globally to make room for someone to win? Will those joining BRI be the ultimate gainers or ultimate losers in this game? Ideological questions are – whether BRI is to be considered as a new avatar of neo-colonialism? What are the potential dangers to the liberal democratic world if China is succeeds through its BRI to control the economic destiny of a good part of the globe? Question closely related to this is – will China try to export its own form of governance model to other countries when it gets in the position to do so? These are some of the vital questions of our era that the academics, contemporary historians, and International relation analysts are compelled to explore.

The term BRI does not stand for any specific project belonging to any specific region or any specific group of nations. It is a very broad concept applied to different parts of the globe involving many nations, regions, and continents where no standard or uniform protocol is applied. Notwithstanding, the sheer size and scope of BRI is indicator of the scale of China’s politico-economic ambition and design. While Beijing portrays the infrastructure development initiative as a benign investment and development programme that is economically beneficial to all parties—and in certain cases it clearly is—there are strategic dimensions that many intellectuals find contradicting this depiction.

Originally conceptualized as a “going out” strategy to secure raw-material, sources of energy and new markets for domestic overcapacity and to diversify China’s foreign asset holdings, Beijing later clubbed together many of its decade old ongoing overseas infrastructure projects, added new ones, stitched them together and renamed them as the “Belt and Road Initiative”17. While the initiative began with a predominantly economic focus, it has taken on a greater geo-strategic and security profile over time.

China’s initiative has attracted over 150 countries and international organizations in Asia, Europe, Middle East, and Africa who have already signed up as active member states under the umbrella BRI projects. International appeal for BRI lies in the fact that it tends to fill the void left by the international financial institutions (IFI) in hard trans-national infrastructure development in the third world. China has been responsive to requests from recipient countries in this area. This adaptability has made BRI attractive to recipient governments despite concerns expressed in many countries.

To this extent, BRI cannot be seen as a traditional aid program because the Chinese themselves do not see it that way and it certainly does not operate that way. It seems to be a purely commercial investment for Chinese businesses to increase its product connectivity. The initiative has a blend of economic, political, and strategic agendas that play out differently in different countries. This is illustrated by China’s approach to resolving debt, accepting payment in cash, commodities, or the lease of assets. The strategic objectives are openly acknowledged by China when it comes to countries where the investment aligns with China’s compulsions to have access to strategic ports and key water ways such as Gwadar in Pakistan, Sihanoukville (SSEZ) in Cambodia, Kyaukphyu (SEZ) in Myanmar, Hambantota in Sri Lanka and Djibouti in the Horn of Africa.

This is the reason critiques feel that behind the facade of BRI, China is flooding strategically important countries in the region with aid and investment to cultivate economic and political dependencies. The motive of funding the dual use civil-military infrastructure is to make the countries dependent on China by imposing interests on long term soft loans which they would not be able to repay in due course and then pressuring host governments to accommodate the Chinese strategic needs. The case of the Chinese funding of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is often cited as an example of this scheme. The leverage China derives from the debt-trap diplomacy is the main objective behind the Belt Road Initiative, so its critiques believe. While the nations are free to accept funds from China based on their own assessments of the potential political, diplomatic, and strategic risks, the critiques of BRI feel that the International Community has the responsibility to take firm steps to make China adhere to the international laws and norms of the EEZs of other nations.

China’s investments in strategically sensitive ports like Gwadar, its development of overseas military base at Djibouti coupled with aggressive posturing in the South China Sea (SCS) have all caused concern to the United States too. Issues related to BRI’s impact on democratic governance of host countries, debt sustainability, and impact on existing global environment and labour standards are being raised by the critiques in many countries inimical to BRI. Internationally, several developing countries, including India, have questioned China’s insensitive transgression of national sovereignty issues related to disputed territories through which some of the BRI projects are planned and under execution18.

A dominant part of US policy makers today prefers to see BRI as a zero-sum game, where every bit of Chinese gain is being perceived to be at the cost of US global primacy. Contradiction of the Spykman & Mackinder’s classical “Rim Land” and “Heart Land” theories are today in full play in the international maneuverings of the two superpowers in their geopolitical strategies. U.S. is formulating its Rim land strategies to counter and contain China and its BRI to defend its encroachments on America’s own turf of global primacy. The American global interests seem deeply threatened by China’s rising power getting manifested on ground through the BRI projects.

Conclusion

Some scholars believe that the right strategy to tackle the rise of China is to accept it and adapt to it sooner than later. Liberal world should make concerted collective international effort to multi-lateralize the whole process of china’s rise which it believes is inevitable. Member nations of European Economic Community appear to gradually get closer to accept this reality and moving towards above position vis a vis BRI instead of going on a collision course with China on the lines of USA. Russia and its Eurasian Economic Community are also supportive of BRI concept and taking active part in it. Russian Chinese collaboration is key to the success of BRI and development of a new Eurasian market system. To that extend, Sino-Russian relation is at its historical best. However, inherent superpower competitive dynamics alone will define this relationship in times to come.

While some others, especially in America and countries aligned to America argue that it is better to adhere to the race-to-the-top dynamic vis-à-vis China. Either strategy requires the democratic world to proactively participate in international infrastructure development programs in the third world and the strategic parts of the world to wrest the initiative from China and to pre-emptively ring-fence areas of strategic concern from future Chinese investments.

The realignment of international relations appears to follow the above contours out of which a new world order and a new balance of power is expected to emerge. Failure to do so is likely to plunge the world in to a phase of confrontation, conflict, chaos and disruptions.

—————————————————————————————————————–

1Parker Geoffrey, August 20, 2015, p. 1, In Defence of classical geopolitics, FPRI Journal of World Affairs, doi: 10.1016/j.orbis.2015.08.006, Institute of World Politics, Washington DC.

2Fukuyama Francis, 1992, p 1, By Way of an Introduction, The End of History and the Last Man , Penguin

3Menon Shiv Shankar,2018, p23,Chapter-I,Choices ,Inside the making of India’s Foreign policies, Penguine

4World Bank,’From Local to Global: China’s Role in Global Poverty Reduction and Future of Development ‘7 December, 2017.

5An Insider Views China, Past and Future, Book review By Michiko Kakutani, May 9, 2011

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/10/books/on-china-by-henry-kissingerreview\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\.html

6“ON CHINA” By Henry Kissinger, Penguin Press.

7 Warner, Jeremy (2014-11-21). “‘Globalisation 2.0’ – the revolution that will change the world”. Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

8 Wei-Wei Zhang, Ideology and economic reform under Deng Xiaoping, 1978-1993 (Routledge, 1996).

9 U.S.-China Trade and MFN Status, C-SPAN, June 12, 1991

10File:///C:/Users/Mehta/Desktop/Article%20for%20Phd/add%20new/China%20-%20Exports%20-%20Historical%20Data%20Graphs%20per%20Year.html

11Jaishankar S,2020, p 29, Chapter-II, The Art of Disruption, The India Way-Strategies for an Uncertain world, Harper Collins

Publisher, India.

12Jan Hoffmann et al., “Review of Maritime Transport, 2016”, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2016.

13John H. Noer and David Gregory, Chokepoints: Maritime Economic Concerns in Southeast Asia (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1996).

14America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company (1942) & Sloan, Geoffrey R. (1988). Geopolitics in United States Strategic Policy, 1890–1987. Harvester Wheatsheaf. pp. 16–19. ISBN 9780745004181.

15Hussini M.M.E. (1987) The Foundations of US Foreign Policy and Strategy. In: Soviet-Egyptian Relations, 1945–85. Palgrave Macmillan, London

16A China-centric economic order in East Asia, John Wong Pages 286-296 | Published online: 02 Nov 2012

17“China and Nordic Diplomacy” edited by Bjørnar Sverdrup-Thygeson, Wrenn Yennie Lindgren, Marc Lanteigne, published in 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Abington, Oxon OX, 144 RN.

18CPEC